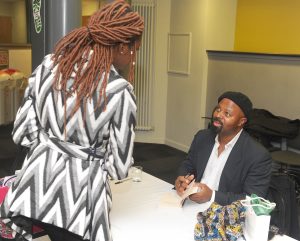

Ben Okri in conversation with Liam Bell. Photo: University of Stirling/Jim Mailer

When Ben Okri walks into Logie lecture theatre, it’s the black beret I see first, ever present in photos of him. It makes me feel as if I have been in his company before; that same sensation you have when you meet someone popular, like a TV personality. A hush falls over the warmly lit, intimate space, as if Azaro, the narrator of The Famished Road, has cast a spell on the students and staff seated in a neat semi-circle.

It’s Tuesday 11th October 2016, the University of Stirling is hosting Nigerian novelist and Booker Prize winner Ben Okri on the 25th anniversary of the publication of his acclaimed novel, The Famished Road. To mark this, the Booker Prize Foundation’s Universities Initiative has made available 1400 copies of the book to all first years; a number that I will later learn is symbolic.

Soon after, Prof Malcolm McLeod, Deputy Principal and Director of the Institute of Aquaculture gives the introductions, expressing gratitude to the Booker Prize Foundation and laying down Okri’s prolific writing career spanning over three decades with eight novels, collections of poetry and essays along the way.

Taking the stage, in conversation with Creative Writing Lecturer Liam Bell, it doesn’t take long for the audience to be transported by the magic of Okri’s insight.

“In Africa, everything is a story, everything is a repository of stories. Spiders, the wind, a leaf, a tree, the moon, silence, a glance, a mysterious old man, an owl at midnight, a sign …” he begins, reading an excerpt from A Way of Being Free. Then he jumps to another page.

I have always known this, have always experienced it back home in Kenya, in everyday life, in conversations on the daily commute, and in the stories of my grandmother. But this still strikes me as profound.

“Unhappy lands prefer utopian stories. Happy lands prefer unhappy stories,” he continues.

The conversation picks up from there, taking usual trajectory of literary conversations: Craft, process, editing oneself, writing and rewriting, the need to toil and discipline oneself in the act of creation.

Then it moves seamlessly to the magic of The Famished Road.

Published when Ben Okri was only 32, the book that would catapult him to worldwide fame is his third. He says it was several years of hard work, in which he had ‘dialogues of form’.

Pausing as if reaching for the right words, holding the tome in his hands, turning it from one palm to another he says, “I was in all kinds of states when I wrote this book. It was frightening writing it, working with logic that is not usual.”

And on the tone, which is at times playful, at times frightening and at times painful, he says, “I wanted a coalition of suffering and laughter and happiness, and to give a voice to the richness of African reality.”

But why can’t Azaro take off, go back to the land where he came from? The land in which he and other spirit children ‘floated on the aquamarine air of love’? Okri says: “That’s the miracle of the paradox of life.”

Perhaps that is why the Booker Prize committee of 1991 thought The Famished Road was the best novel of that year: the transcendental nature and fullness of its experience. Something that he’s felt more African writers need to embrace for their writing to achieve greatness

Okri says the book had sold about 2000 copies before the Booker came along, and looks over to his editor for confirmation. He’s told, no, not really. Only 1400 copies. The audience roars with laughter. And it strikes me that Ben and his editor have a rare relationship; one that has lasted for over 25 years and is still going. Editors and writers can, in fact, be lifelong friends.

Of the pressure that came with prize, the most difficult was shutting out the achievement and staring at a new blank page. Writing new stories, because that is the life of the writer. Okri winning the Booker opened up UK publishing for other black and ethnic minority writers, even though diversity is yet to be achieved according to a report by Spread the Word.

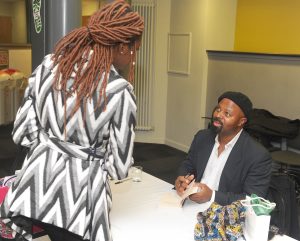

In the Q&A that followed, he amuses us by saying he writes while standing. And then it’s the end, the room empties, and Ben Okri signs books for audience members.

Like the last line in The Famished Road, ‘A dream can be the highest point in life.’ This feels like one.

Ben Okri chats with a student as he signs her book. Photo: University of Stirling/Jim Mailer

By Otieno Owino